21 July 2021

Greg Mifsud – National Wild Dog Management Coordinator

A movement by landholders wanting to protect dingoes on their properties is all good and well, but the question of how the wild dogs will be stopped from moving onto other properties is something they need to consider.

In response to the ABC’s recent 7.30 report, One Man’s Pest, we acknowledged the cattle grazier featured was using management techniques to control wild dog or dingo attacks on his livestock by shooting those known to be killing calves.

The approach taken by the cattle grazier interviewed actually reinforces the approach taken by the National Wild Dog Action Plan to control the dogs actually causing the impact.

The National Wild Dog Action Plan is about reducing the impact and controlling wild dogs to mitigate that risk.

Management strategies for wild dogs on cattle properties will vary depending on production systems, husbandry practices, and environments.

A nil tenure approach of strategic on-ground wild dog management has been shown to be the most successful method of minimising agricultural, economic and environmental impact.

There is an expectation under the Queensland Biosecurity Act (2014), and through good neighbour relations, that producers will manage their wild dog numbers so as to cause limited risk to neighbouring properties.

This is carried out under the local Wild Dog Management Plans, which reinforce and validate the approach.

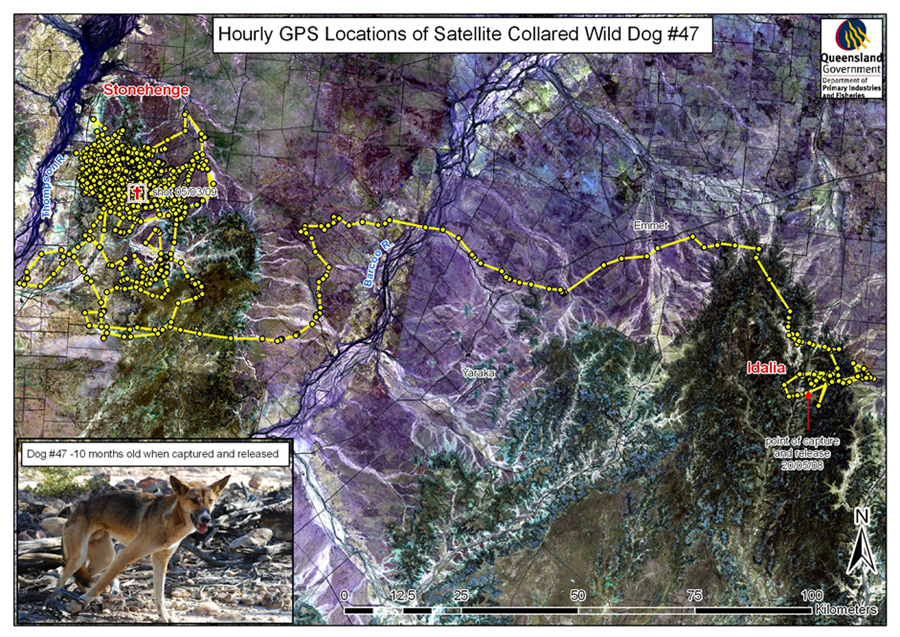

Radio tracking data collected from wild dogs in western Queensland revealed some dogs can travel in excess of 100km so it’s important wild dogs are controlled in those regions where sheep and cattle production occur side by side.

Wild dogs and dingoes will quickly reach a carrying capacity and once that is established, any offspring produced after that, particularly males, will be chased out of their parent’s home range prior to the breeding season.

These young animals can move great distances looking for a vacant territory and can cause problems for sheep producers.

So, while some landholders may want to keep dingoes or wild dogs on their properties, they will have to consider how they manage any dispersal from their property to other properties across the region where those dogs may cause significant impacts on other livestock producers.

The highly mobile nature of wild dogs is why the plan advocates the need for a strategic landscape scale approach to management.

This does not mean a blanket baiting across the landscape but rather targeted control on movement corridors or where wild dogs were active using best practice techniques.

The evidence is clear wild dogs are causing impacts on cattle producers in northern Australia.

On properties where they undertake pregnancy scanning of cows and know how many calves to expect at marking, wild dogs are killing between 5 and 10 per cent of calves annually.

Other impacts, such as dog bites on calves that survive being attacked and wild dog borne disease, cause additional economic losses to cattle producers and processors across the country.

Queensland’s Northern Australian beef fertility project, CashCow, revealed foetal/calf loss was five per cent higher in areas where wild dogs were considered by property owners/managers to be adversely impacting on herd productivity.

Share